How are Scotland’s towns and cities performing as retail and leisure destinations?

On November 28th, was the Local Data Company’s (LDC) fifth Scottish Retail and Leisure Trends Summitheld in partnership with the University of Stirling. The report revealed interesting insights as to how Scottish centres are performing relative to England and Wales but also relative to each other. There was also a short presentation by Chris Fowler of LDC on how data is being captured and used at a local level to understand performance and opportunity with a case study from Aberdeenshire Council on the town of Peterhead.

The report findings were presented by Professor Leigh Sparks of the Centre for Retail Studies at the University of Stirling off the back of which there was an excellent panel discussion (see panellists above) as well as questions from the audience. The key findings can be summarised as follows:

- The Scottish retail and leisure vacancy rate is currently 11.9%, a +0.2% increase on the rate in 2016 – this is the first year-on-year increase in Scottish town centre vacancy in five years.

- Overall retail vacancy in cities and towns now averages 12.3%, down from 12.6% in 2016 and has reduced significantly since 2013 when rates were 13.4%.

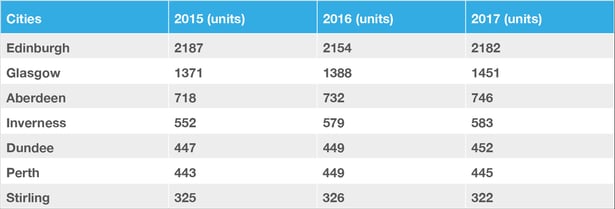

- Glasgow and Edinburgh continue to dominate the retail scene in Scotland accounting for 15.7 % of all retail premises.

Figure 1. Number of retail premises across Scottish cities in

Figure 1. Number of retail premises across Scottish cities in

2015, 2016 and 2017 (Source: LDC)

- Scottish towns and cities have seen a fall in retail vacancy but a rise in leisure vacancy.

- Retail park vacancy has decreased from 7.8% in 2016 to 6.7% in 2017 although this remains the highest retail park vacancy rate across GB.

- Shopping centre vacancy rates have also improved from 16.9% to 15.1% – the largest reduction in shopping centre vacancy across GB – which can potentially be attributed to modernization of older centers across Scotland, with an increased focus on leisure.

- Across the sixty six shopping centres measured, 20 have more than a 20% vacancy rate, with the highest being Callendar Square in Falkirk at 64.9%.

- Edinburgh continues to have the lowest Scottish city vacancy rate of 8.2%.

- Dundee has the highest level of Scottish city vacancy at 21.7% although this is an improvement on 2016. It also remains the city with the highest persistent vacancy at 9.7%.

- There has been progress in persistent vacancy overall in 2017 with 11 of 124 towns showing persistent vacancy of over 10% versus 17 towns in 2016.

- There are 20 Scottish towns with 0% persistent vacancy including St. Andrews, Aviemore, Gretna, Inverurie and Biggar.

- Leisure continues to grow in Scotland, accounting for 26.7% of the total retail/leisure premises, an increase from 26.4% on last year.

- Cities are becoming more leisure orientated at a faster pace than towns.

- Across both cities and towns, the proportion of independent retailers is increasing whilst the proportion of multiples in decreasing. Independent retail in cities has grown from 54% to 57% since 2013 whilst towns have grown from 53% to 55% over the same period.

- Edinburgh and Perth are the cities with the highest percentage of independent retail at 69% and 67% respectively.

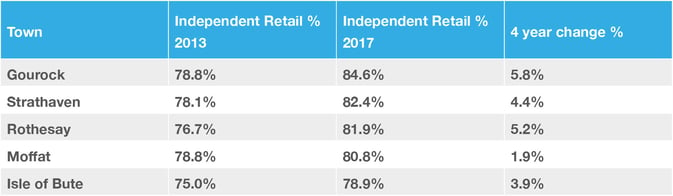

- Four towns have over 80% of the retail offer as independent retail; Moffat, Strathaven, Rothesay and Gourock (which had the highest level of independent retail at 84.6%).

Figure 2. Top five Scottish towns by the number of Independents as a percentage

Figure 2. Top five Scottish towns by the number of Independents as a percentage

of the total units in 2017 (Source: LDC)

- Convenience shopping has increased across both cities and towns year on year since 2013.

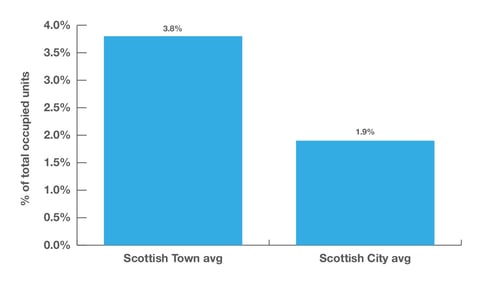

- The 2017 BMG index highlights that since 2013, all three areas have reduced resulting in the town BMG index dropping from 4.9% in 2016 to 3.8% in 2017; whilst the city index dropped from 3.0% to 1.9% over the same period – an indicator that new legislative control is having a positive impact.

Figure 3. Average BMG score for Scottish Towns compared

Figure 3. Average BMG score for Scottish Towns compared

to Scottish cities in 2017 (Source: LDC)

The panel discussion was wide ranging but key themes that I took away included;

- The costs for retailers keep rising (or the profits keep dropping!) as a result of legislative changes, business rates, government levy’s and minimum wage policies and all of that is before one considers rents.

- Challenges are on the increase from the uncertainty of Brexit, currency devaluation, more demanding shoppers, less shopper loyalty and consumers being short of time but spoilt for choice.

- Towns are a critical part of the economy and communities and exist as a ‘place to come together’ as well as being a ‘reflection of the people who live there’. Irvine was cited as an interesting example of a town that has a high street, shopping centre and retail park all sitting next to each other and competing with each other but where the council has a strategy and plan to raise the attractiveness and health of the town.

- The last five years have seen significant repositioning and restructuring within many towns and cities (but not all) and that physical stores have a key role to play and this is seen by continued openings and refurbishment of space.

- Retailers have trained the customer to not buy at full price which is creating year- round discounting and heavily impacting profitability.

- We just have too many shops for modern retailing needs (and continue to build more) so we need to find alternative uses for these buildings that will contribute to the vibrancy of towns.

- Towns and cities are on different trajectories when it comes to evolution and change.

- Having a physical store presence is a key driver for online sales and the growth of click & collect illustrates this. Product differentiation by online and offline purchases needs to be recognized when it comes to what you display instore as impossible for many to show their full inventory in a physical space. Use of digital enables you to have smaller stores to assist in inventory display.

Professor Leigh Sparks summarised what the report was saying as follows;

“Town centres are always changing and it is vitally important to monitor and understand the dimensions of this change. The data from the local Data Company show that the process of adjustment and change across Scotland’s towns and cities continues but is not uniform.

The headline vacancy figure for towns has risen in the last year but this masks a decline in retail vacancy and a rise in leisure vacancy, the latter for the first time since this series began. We have also seen a decline in the number of charity shops. These two sectors are ones which have expanded rapidly in Scotland in recent years, and the data poses the question whether this year’s changes are a pause in expansion or a reverse?

Within the data there are many examples of towns which have been restructuring and redeveloping and thus a focus on one year’s snapshot vacancy figures are unhelpful. Overall, retail vacancy across Scotland continues to fall.”

My conclusions would be that the report reflects the structural changes that are taking place UK wide.

Whilst town centre vacancy rates have stabilised they have not shown the improvement that shopping centres and retail parks have shown, which for some therein lies the challenge.

As with all of LDC’s data the devil is in the detail as well as understanding the wider context. An example is that whilst Scotland’s shopping centres have more occupied shops that in previous years they still have more empty shopping centre units than England and Wales. Is this as a result of oversupply, underdevelopment or that high streets and retail parks are the core destinations for consumers?

The report also evidences the changes taking place in shop occupation in Scotland, with fewer comparison goods shops and more food & beverage and service (e.g. health & beauty) outlets. The reduction of charity shops is worthy of note, as is the reduction in the number of Booze, Money and Gambling outlets (BMG). This is one that many might not expect, but is something that has been a focus for the country’s politician’s and public health organisations.

The changing nature of places and how they serve the modern consumer is clearly evident in this report. An understanding of these changes and alignment to a plan at each and every town level is key to maintaining the relevance and value of Scotland’s towns. As with evolution it is important to maintain a mind-set of adaptability in such a fast-changing world. There remains an oversupply of traditional shops in Scotland, as elsewhere in the UK, but what is clear is that maintaining a physical connection is something that consumers do and will continue to value and support through physical store visits.

I would like to make a final vote of thanks, as this will be my last Scottish Summit as I move on from LDC at the end of the year, to Leigh Sparks and his colleagues at Stirling (Anne Findlay and Lorraine Ferguson) for working with LDC to create evidence research and insight on Scotland’s towns, cities, shopping centres and retail parks which did not exist previously. By having a foundation of solid data, academic rigour in its analysis and a willingness to share the findings I believe all stakeholders in Scotland’s places can, and will, make better decisions in the future for the good of all. Final thanks is due to KPMG (and especially David McCorquodale) for hosting this event for the last five years in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Leave a comment: