Wellbeing and real estate: the sector’s next frontier?

The first in a series of short articles aimed at introducing wellbeing concepts and ideas to real estate investors: why it matters, what it is and how they can drive improvements in it. They are primarily aimed at UK audiences but will hopefully be of interest more widely.

This article has been written by Tim Francis.

The critical role for businesses in improving wellbeing

“What we measure affects what we do; and if our measurements are flawed, decisions may be distorted”

Stiglitz, Sen & Fitoussi, “Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress”, European Commission, 2008

Governments, institutions and businesses around the world are discovering that it is not enough to report on aggregate measures of economic and financial performance. Measuring the environmental and societal impact of policies, and in return-on-investment (ROI) appraisals, has become vitally important. A landmark report, written in the teeth of the Global Financial Crisis, made a persuasive case for looking beyond GDP at more insightful measures of prosperity and societal progress [1]. Since then various geopolitical, economic and societal trends have given greater weight to the ‘Beyond GDP’ movement.

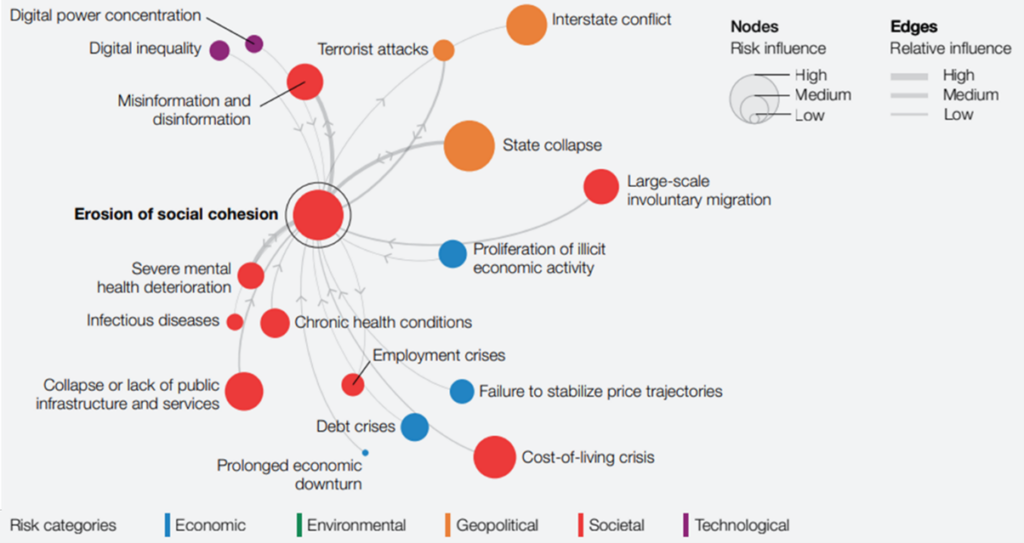

Yet societies are becoming more polarised and trust in governance structures is eroding. Social divides are widening on many issues, not only income and wealth inequality. The World Economic Forum (WEF) in its latest Global Risks Report (2023) notes that “issues such as immigration, gender, reproductive rights, ethnicity, religion, climate and even secession and anarchism have characterized recent elections, referendums and protests around the world”. Its survey found that “erosion of social cohesion and societal polarisation” was the fifth-most severe global risk in the short term, and at the heart of a worrying risk network.[2]

Eroding social cohesion is at the heart of a dangerous socio-geopolitical-economic risk network (WEF).

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Risks Perception Survey 2022-2023.

Many of these societal risks aren’t particular to rich or poor countries. What’s more, they are leading to unpredictable policy making and increasingly insular attitudes across the world. A concern highlighted by WEF is that global collaboration efforts on critical challenges like climate change and the transition to a net zero world could be limited as a result. Meanwhile, the risks of state collapses or interstate conflict are higher, all posing threats to businesses and investors seeking long-term stability.

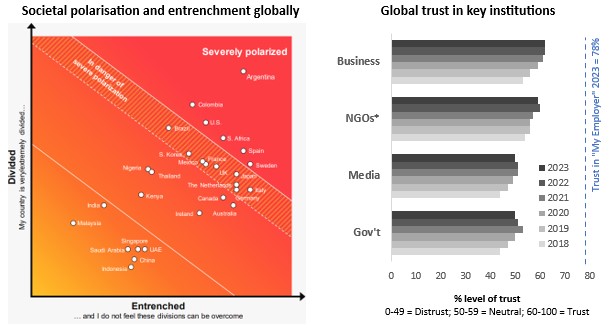

Societal polarisation is also forming a vicious cycle of distrust for institutions around the world. That’s being driven by the sharp decline of economic optimism about the medium term, according to Edelman’s latest Trust Barometer. Persistently high inflation and rising interest rates across the world are contributing to that sense of gloom. The survey revealed that in many advanced democracies, societal divides were perceived to be both significant and entrenched, as polarisation and distrust seem to be feeding off each other.[3]

Source: 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report (2018-2023).

The polarisation/entrenchment matrix plots the % of respondents answering very divided or extremely divided to the question “how divided on key societal issues you believe your country is today” on the y-axis, against the % who had a negative or neutral response to the question “How likely or unlikely do you think it is that your country will be able to work through or overcome its ideological divisions and lack of agreement on key issues and challenges?” on the x-axis.

For the % level of trust respondents were asked “please indicate how much you trust [that institution] to do what is right” rating on a 9 point scale. * NGO = Non-Government Organisations.

It’s notable that trust in business exceeds other key institutions, especially government and the media. Edelman’s survey showed that expectations about the societal impact of businesses were rising, particularly on climate change and economic inequality. Business leaders are now widely expected to take a public stand on ESG matters and to work openly and transparently alongside policy makers. The survey also suggests they have a greater licence to hold the forces of division to account, although they must also take care to avoid the perception of politicisation. That is bringing into the spotlight corporate views and actions on social impact, with the “S” of ESG increasingly coming into focus.

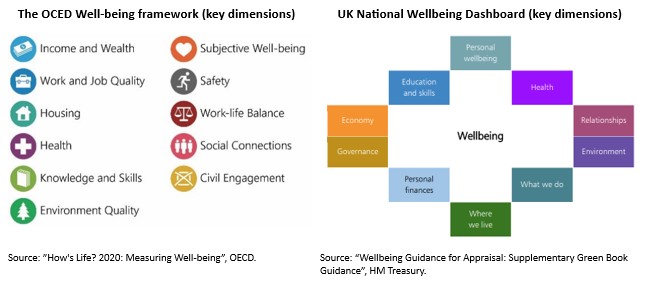

All of this highlights the importance of understanding and acting on the pressures bearing down on citizen wellbeing. There is an increasingly urgent need for institutions—including businesses—around the world to measure, openly report and find ways to improve it. The academic community has made a lot of progress in the past fifteen years on understanding wellbeing and quality-of-life (QoL). Strategic frameworks and social impact indicators are emerging at international and national level. For example, the OECD’s Better Life Index brings together comparative data for many countries; The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal #3 sets clear targets for a range of wellbeing and QoL indicators [4]. Many countries have adopted similar approaches, such as the UK’s National Wellbeing Dashboard which follows similar lines to the OECD’s (see graphic below).

Importantly, these approaches are starting to influence policy making and public spending decisions at the local level. In the UK, HM Treasury published a detailed supplementary guidance for its “Green Book appraisal” in 2021 [5]. It explains “where, when and how wellbeing concepts, measurement and estimation may contribute to the appraisal of social, or public value”. Public spending is increasingly being tied to the value attributed directly to social impact based on wellbeing measurement. It’s likely that private sector investment decisions will start to adopt a similar approach.

The time of the “S” in ESG has arrived. Wellbeing and quality-of-life indicators have a big role to play in shaping, measuring and assessing policy impacts. Academics at University of Cambridge and the Bennett Institute for Public Policy note that “wellbeing is increasingly advocated as a more appropriate target for shaping public policy than conventional economic metrics, and has attracted significant policy attention and advocacy.” [6] Yet they also observe that better understanding of the causal relationship between aspects of wellbeing and other variables would lead to more effective policy making and reduce unintended consequences.

In order for policy makers and businesses to base decisions on social value with increasing confidence, it is vital to build on existing wellbeing theories and evidence. In the built environment sector that means:

– improving how we understand wellbeing theory and the associated data,

– measuring wellbeing consistently and more widely, within buildings, across neighbourhoods and for multiple stakeholder groups, including residents, workers and visitors,

– developing logical theories of change about the causes and effects of investment and wellbeing in the built environment, and

– using- this body of work to inform better investment and development decision making, and build stronger relationships with the communities we serve.

Future articles will look at wellbeing theories and emerging best practice frameworks in the public and private sectors, focusing on how they relate to real estate and the potential implications for investment and development strategies-.

[1] The report notes that “when there are large changes in inequality (more generally a change in income distribution) gross domestic product (GDP) or any other aggregate computed per capita may not provide an accurate assessment of the situation in which most people find themselves. If inequality increases enough relative to the increase in average per capital GDP, most people can be worse off even though average income is increasing”. Link here.

[2] WEF defines this risk as “the loss of social capital and fracturing of communities leading to declining social stability, individual and collective wellbeing and economic productivity. See Global Risks Report 2023, page 23. Link here.

[3] “2023 Edelman Trust Barometer, Global Report”, Edelman. Link here.

[4] Goal 3 is “Good health and well-being”, specifically to “ensure health lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”. Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development Goals. Link here.

[5] See Source: “Wellbeing Guidance for Appraisal: Supplementary Green Book Guidance”, HM Treasury. Link here.

[6] “Wellbeing Public Policy Needs More Theory”, Fabian, Agarwala, Alexandrova, Coyle, Felici, University of Cambridge and Bennett Institute for Public Policy Cambridge, June 2021. Link here.